“My English isn’t good enough.”

“I need to be home my junior year for corporate head hunters to offer me a post-graduation job.”

“I don’t care to leave Japan.”

These are a few of the rationales I’ve heard as a recruiter for a Midwestern university for why Japanese students don’t want to study in the United States. As a former English teacher through the Japan Exchange and Teaching (JET) Program—an initiative of the Japanese government importing native English speakers to Japanese classrooms—I was optimistic my familiarity with the language and educational system would enable me to entice Japanese students to come study at my university. Tuition is relatively affordable, the location is highly livable, and studying abroad is the experience of a lifetime. However, I soon discovered optimism and a ready list of selling points weren’t enough to overcome entrenched barriers for students to leave Japan for college.

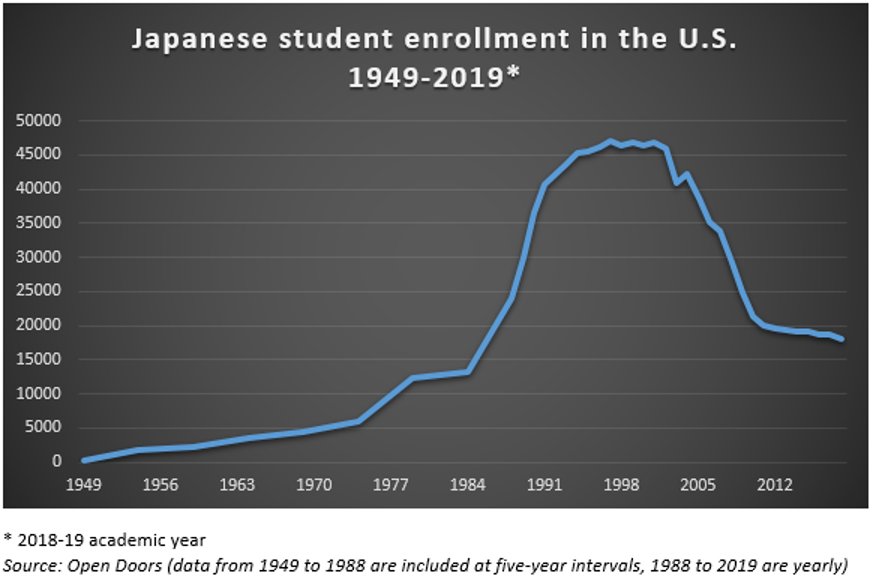

Japanese student enrollment in the United States grew steadily from 1949 until 1997, plateaued in the ‘90s, then fell precipitously. In the 2018-19 academic year, 18,105 Japanese students were studying in the United States—the lowest number in more than 30 years—and only 38% of the record high of 1997 (47,073).

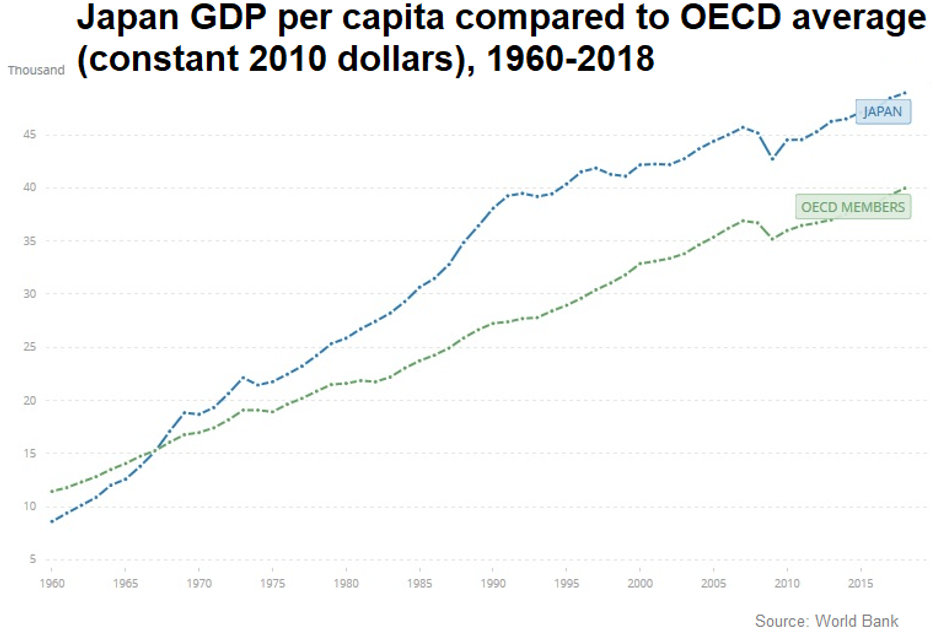

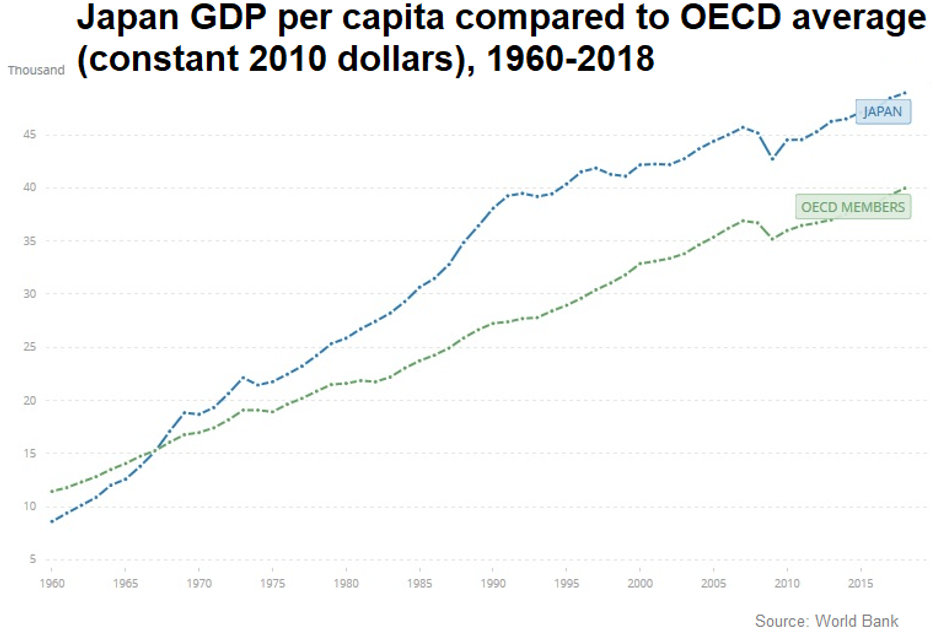

One explanation for declining enrollment is Japan’s long-stagnant economy. While Japan’s asset price bubble of the mid-‘80s likely explains the 209% increase in Japanese students from 1984 to 1991, the bubble’s burst doesn’t fully explain the drop-off. Factoring for Japan’s declining population, GDP per capita in constant 2010 dollars has kept track with the OECD average.

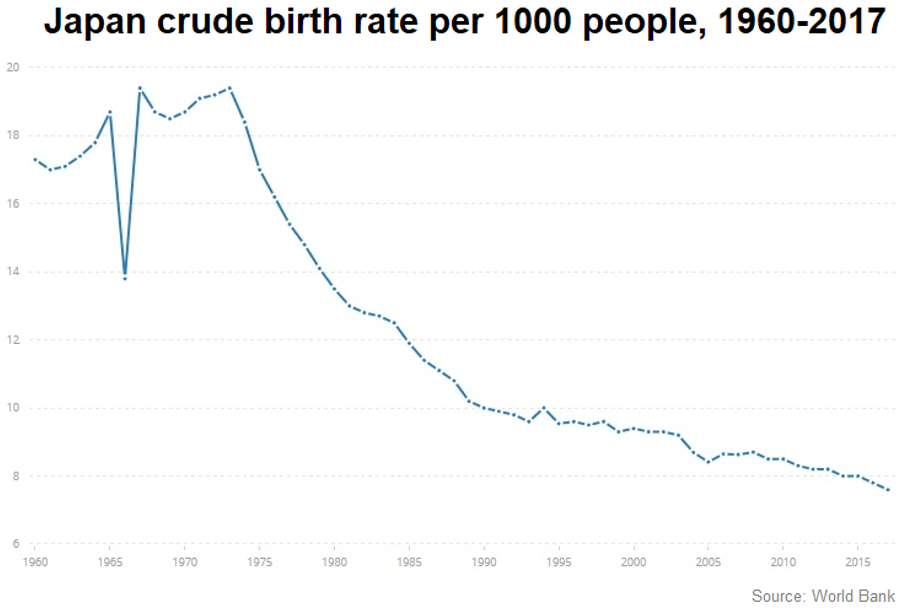

I contend Japan’s declining birthrate better explains the decline. In 1973 (when the 1991 freshman cohort would have been born) Japan’s crude birthrate was 19.4 births per 1000 people. In 2000 (the birth year of the 2018 freshman cohort) the corresponding birthrate was 9.4—just 48% the rate of 27 years earlier. Consequently, enrollment for the 2018 cohort was 44% the size of 1991’s. In other words, if the proportion of Japanese students choosing to study in the United States remains constant, the number of students in the United States would mirror the birthrate after a lag of roughly 18 years. Looking at the enrollment graph above and the birthrate graph below, one can see the shape of the curves are similar.

As university recruiters can do little to reverse the declining birthrate, they should instead focus on the concerns voiced by students themselves.

When young Japanese students say they don’t want to leave Japan, reading between the lines they really mean they perceive the United States is dangerous and studying in such a place is unimaginable. Given typical headlines about the United States don’t paint our country as a particularly welcoming or safe place, and the music and movies we export do little to dispel this image, this is an understandable concern. One way to overcome this is for universities to develop short-term exchange programs or ESL courses. While studying in the United States for four years may seem unimaginable, coming for one semester sounds less threatening to students and their parents. Once on campus and realizing their fears are overblown, the idea of sticking around for a degree is more realistic. Short-term ESL programs can also help students who fear their English skills aren’t strong enough to study abroad.

To counter the objection, students need to be home their junior year to be recruited for a job, university representatives can point out the number of Japanese corporations with offices in the United States. University career counselors can connect students with those companies to help them get their feet in the door of Japanese employers.

Dustin Dye is the Transfer & Agreement Project Manager at the University of Missouri-Kansas City. He was an Assistant Language Teacher through the Japan Exchange and Teaching Program from 2008 to 2011 in Akaiwa, Okayama.

This article is part of a guest-contributor partnership between the East-West Center in Washington and the United States Japan Exchange & Teaching Programme Alumni Association (USJETAA) in which former JET participants contribute articles relating to their experiences in Japan.

The USJETAA is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit educational and cultural organization that promotes grassroots friendship and understanding between the United States and Japan through the personal and professional experiences of over 30,000 Americans who have participated on the JET Programme since its inception in 1987. USJETAA serves as a resource for individual JET alumni, JETAA chapters nationwide, and potential JET participants; supports the leadership of JETAA chapters with programming, membership recruitment, chapter management, leadership, professional development, and fundraising; and, supports the JET Program(me) and engages with the U.S.-Japan community.